Kafka's Second Life

Wherein we delve into the diaries of a young Franz Kafka. It’s Prague, 1910, and anxieties abound. Body horror? Check. Creative constipation? Check. Bad trip to Paris? Oh, yeah.

Before we took our detour to Prague, we left Kafka at the end of 1909, when he published his early reportage about the Brescia airshow. So now, let’s resume our exploration of Kafka’s early years.

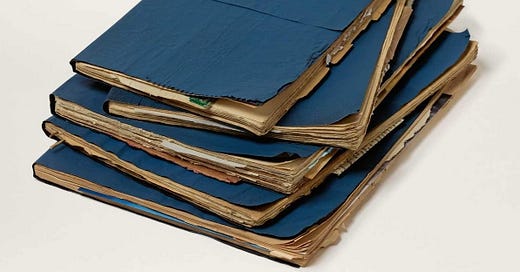

In the early months of 1910, Kafka, spurred on by his toady, Max Brod, took up a new practice which would give his writing a definite leg-up: keeping a diary. Actually, he kept several diaries—if you read Ross Benjamin’s recent translation (based on the 1990 Hans-Gerd Koch edition), you’ll soon realise that Kafka was writing in several journals simultaneously, often jumping around between them and scribbling down the tiniest detail. Many entries are undated or incomplete. Once decoded and pieced together, however, these diaries reveal Kafka’s everyday mundanities, from what he had for lunch to the plays he watched at the cabarets to the books he read, yodel-ay, yodel-ay...

But the most striking aspects include his fragmented reflections, thoughts, dreams, struggles, where he dissects his physi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paper Knife to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.