When the Son Becomes an Unclean Animal

Metamorphosis, episode 2. In which we explore how Gregor Samsa's transformation into an 'ungeheures Ungeziefer' makes him a failed sacrifice, trapped between familial duty and crushing debt.

‘Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt.’

So begins, in medias res, Franz Kafka’s most famous story, with what is arguably one of literature’s most memorable opening lines—in a way redolent of Dante’s Inferno’s opening line: ‘In the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself lost in a dark wood’.

Here is Kafka’s transformation (reversal, one could argue) of that classic opening: ‘When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into some sort of monstrous insect.’1

We should pay attention to that particular phrase, ungeheueren Ungeziefer. Possible translations include:

‘gigantic insect’ (E&W Muir)

'monstrous vermin' (Corngold, Neugroschel)

‘some kind of monstrous vermin’ (Crick)

‘monstrous cockroach’ (Hofmann)

‘enormous bedbug’ (Moncrieff)

‘monstrous insect’ (Bernofsky)

‘large verminous insect’ (Williams)

Ungeheuren Ungeziefer has no literal translation in English, but broadly means ‘an enormous or monstrous kind of unclean vermin.’

Over the past century, this novella has garnered countless interpretations, from psychoanalytic readings focused on Kafka’s/Samsa’s Oepipal complex and relationship with his domineering father to Marxist analyses of lumpenproletariat alienation under bureaucratic capitalism. Yet despite the overwhelming abundance of scholarship, I believe few critics have fully explored (I’m happy to be proven wrong; if so, please comment below) how the novella’s opening chapter establishes a complex meditation on debt and sacrifice—themes that provide fascinating insights into Gregor’s tragic transformation. That is what I’ll endeavour to do here and in the upcoming episodes.

The German phrase ungeheuren Ungeziefer, as demonstrated above, has proven particularly troublesome for translators. As Susan Bernofsky notes in her excellent New Yorker piece:

The epithet ungeheueres Ungeziefer in the opening sentence poses one of the greatest challenges to the translator. Both the adjective ungeheuer (meaning “monstrous” or “huge”) and the noun Ungeziefer are negations—virtual nonentities—prefixed by un. Ungeziefer comes from the Middle High German ungezibere, a negation of the Old High German zebar (related to the Old English ti’ber), meaning “sacrifice” or “sacrificial animal.” An ungezibere, then, is an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice, and Ungeziefer describes the class of nasty creepy-crawly things. The word in German suggests primarily six-legged critters, though it otherwise resembles the English word “vermin” (which refers primarily to rodents). Ungeziefer is also used informally as the equivalent of “bug,” though the connotation is “dirty, nasty bug”—you wouldn’t apply the word to cute, helpful creatures like ladybugs.2

This etymology is crucial for understanding the novella’s deeper themes. Gregor’s transformation doesn’t simply make him revolting or monstrous—it specifically renders him unfit for sacrifice. Yet paradoxically, as we will see, his new form perfectly embodies his role as a modern-day scapegoat, trapped between familial duty and crushing debt.

With all this, we understand from the start that, contrary to Dante, Gregor will never exit his Inferno, never glimpse the Empyrean from his bedroom window.

Being ‘unfit for sacrifice’ carries profound implications in Kafka’s story. In traditional religious contexts, sacrificial animals had to meet strict criteria of purity and perfection. This concept is particularly prominent in Islam and Judaism (see Leviticus and Deuteronomy), where animals such as pigs, birds of prey, reptiles, shellfish, molluscs, insects, are considered ‘unclean’. And so, an animal deemed ungeziefer, ritually unclean, was therefore regarded as unsuitable for offering to the divine. By describing Gregor with this specific term, Kafka immediately establishes a connection to sacrificial traditions while simultaneously subverting them.

So, has Gregor turned into a cockroach, a beetle, a woodlouse, a centipede, a scorpion, a crab, or some other form of arthropod? In his lectures on literature, Vladimir Nabokov insists on precision when discussing Gregor’s new form: ‘Now what exactly is the ‘vermin’ into which poor Gregor, the seedy commercial traveler, is so suddenly transformed? It obviously belongs to the branch of “jointed leggers” (Arthropoda)... We shall therefore assume that Gregor has six legs, that he is an insect.’3 Yet, while Nabokov’s entomological specificity is interesting (he himself was, I believe, an expert lepido/coleopterist), it completely misses, as we’ve just seen, the deeper significance of Kafka’s chosen terminology.

The choice of ‘vermin’ as Gregor’s transformed state carries additional weight given both personal and political contexts. As Reiner Stach notes, this imagery emerged directly from Kafka’s childhood experiences:

The image of a person degraded into an animal had been familiar to him for some time, probably since his childhood. His father, who liked to pepper his speech with profanities, employed this device on a regular basis. Their clumsy cook was a “beast,” the consumptive shop-boy a “sick dog,” the son making a mess at the table a “big pig.”4

Hermann Kafka even disparaged Franz’s friend, Yitzhak Löwy, with the remark, ‘If you go to bed with dogs, you wake up with fleas.’ In transforming these casual dehumanising insults into literal metamorphosis, Kafka exposed the violence inherent in such language. Moreover, this terminology carries dark political resonances. The language of ‘vermin’ and ‘parasites’ has historically been deployed in political discourse to justify violence against targeted groups, preparing the ground for their persecution by first linguistically stripping them of their humanity.

, a fellow Substacker, recently noted: ‘some language Trump uses comes directly from the 1930s. Not just Hitler but Stalin, Mao and the East German Stasi liked to talk about their enemies as vermin and parasites who “poison the blood” of the nation.’5 By making such metaphorical dehumanisation literal in his story, Kafka illustrated how everyday degrading language can pave the way for actual violence against scapegoated individuals and groups.Therefore, the horror of Gregor’s situation stems not from his specific biological classification, but from what his new form represents—a being that exists outside the bounds of acceptability and, more specifically, outside of acceptable sacrifice. As René Girard argues in La Violence et le Sacré6, a sacrifice serves as a mechanism for channelling societal violence onto a designated victim or scapegoat, thereby appeasing tensions and preserving social order. But Gregor’s transformation makes him simultaneously the perfect and the impossible scapegoat: perfect because he bears the community’s (his family’s) burdens, impossible because his very nature renders him ritually unclean.

One step further: Kafka wastes no time connecting Gregor’s transformation and his financial obligations. Even before fully processing his new physical state, Gregor’s thoughts immediately turn to his work and the debt he must repay, highlighting the close, albeit ambiguous, relationship between his job and his transformation into a bug: ‘If I didn’t have to hold back for my parents’ sake, I’d have given notice long ago... as soon as I’ve saved up enough money to pay back what my parents owe him [his boss]—another five or six years ought to be enough—I’ll most definitely do just that.’

This fixation on debt and the need to repay by the sweat of one’s brow is far from incidental; in fact, in my view, this is key to understanding the story.

Coming from a bourgeois family, Kafka was intimately familiar with the pressures of financial obligation. As we’ve seen in my previous post, a few weeks before he began writing The Metamorphosis, Kafka witnessed his family’s struggle with the failing asbestos factory, leading to intense family pressure on Franz to take a more active role in saving the business. As Reiner Stach notes:

It became apparent just a few months after the start of production that they had completely miscalculated their finances. The capital basis was insufficient and had to be built up, but Hermann Kafka was unwilling to keep putting in money; he saw Elli’s dowry and Franz’s share seeping away irretrievably.

Gregor’s situation mirrors this dynamic, though with a crucial twist. Unlike Kafka, who resisted involvement in his father’s business venture, Gregor has fully submitted to his role as the family’s financial saviour. He works as a travelling salesman for the very firm to which his father owes money, transforming filial duty into a form of indentured servitude. The debt becomes both literal and symbolic—a financial burden that morphs into a sacrifice of identity and autonomy.

The parallels between Gregor’s situation and the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac (the Akedah) are also striking, though inverted in telling ways. In Genesis 22, God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac, only to provide a ram as a substitute at the last moment. Isaac is spared precisely because a suitable sacrificial animal is found. But in Kafka’s modern retelling, Gregor’s transformation into an ungeheuren Ungeziefer represents a perversion of this substitution—instead of being replaced by an animal, he becomes one. And not just any animal, but one vile, unspeakable, despicable, specifically unfit for sacrifice.

This inversion speaks to the novella’s broader critique of modern systems of exchange and obligation. As Girard observes, ancient sacrificial mechanisms served to channel and contain violence within society, curb the endless escalation of reciprocal revenge and retaliation, quell the vicious cycle of talionic law. But in the secular world of The Metamorphosis, these traditional structures have broken down. Gregor’s sacrifice lacks divine sanction or ritualistic meaning—it is merely the grinding obligation of debt repayment stretched across ‘five or six years’ of soul-crushing work: this is precisely what ends up turning him one morning into that monstrous, unclean animal; and its very uncleanliness reveals that Gregor’s sacrifice was indeed ineffective in repaying the debt passed down from father to son. In fact, it is possible that Kafka, in this text, is looking deep into the concept of ‘infinite debt’ that Nietzsche introduced in the Second Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality—which opens another avenue that I’ll probably explore in an upcoming post…

For now, let’s not get too speculative! I’ll simply highlight some of the most striking aspects of this first chapter that come to mind and may or may not align with my central hypothesis.

Upon discovering his transformation, Gregor’s first thoughts are not of astonishment or crisis but of mundane logistics, as if nothing significant had changed, as though everything was almost business as usual: ‘The next train was at seven o’clock; to catch it, he would need to rush like a madman, and his sample case wasn’t even packed yet’. This focus on practical concerns in the face of an impossible situation creates a weirdness that characterises what Tzvetan Todorov calls ‘the fantastic’—a hesitation between natural and supernatural explanations that forces readers to question their assumptions about reality.7

Let’s also note the progressive breakdown of Gregor’s ability to communicate. His transformation affects not just his body but his voice, which becomes increasingly unintelligible to others. It becomes ‘unmistakably his old voice, but now it had been infiltrated as if from below by a tortured peeping sound that was impossible to suppress.’ This ambiguity, duality or hesitation—simultaneously human and inhuman—reflects his position, caught between filial/professional duty and personal annihilation.

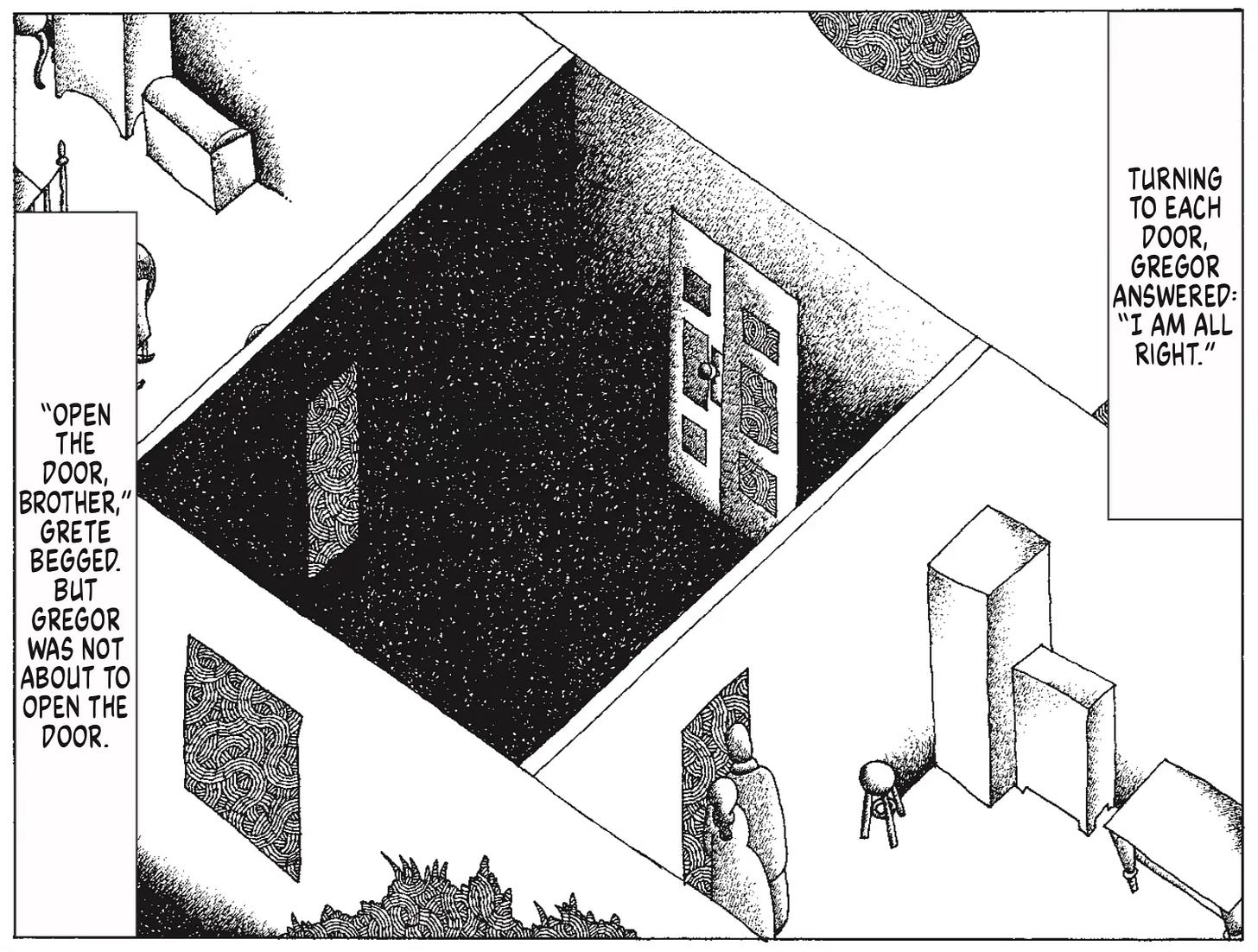

As the family begins to gather outside Gregor’s doors, their attempts to communicate with him become increasingly tense:

already his father was knocking at one of the room’s side doors, softly, but with his fist: “Gregor, Gregor,” he called. “What’s the problem?” And after a short while he repeated his question in a deeper register: “Gregor! Gregor!” Meanwhile, at the other side door came his sister’s faint lament: “Gregor? Are you unwell? Do you need anything?”

The family’s inability to understand Gregor’s speech, despite his perfect comprehension of theirs, creates a one-way relationship that characterises the underdog and potential victim of collective violence. His sister Grete’s plea through the door becomes painfully ironic, as his new condition makes it impossible to articulate his needs. He is, from now on, literally at their mercy.

Let’s now take a look at the setting. The story primarily takes place in Gregor’s bedroom, translating that transitional interval between nightmare and reality into the spatial characteristics of the room, situated between the living room and his sister’s bedroom, with one door on either side of Gregor’s bed.

It’s worth noting that, similar to ‘The Judgment,’ where Ottla recognised the layout of the Kafkas’ flat—observing that the father’s bedroom was located where the toilets were in reality!—Gregor’s bedroom is also positioned between two other rooms, just like Franz’s bedroom (which he once called ‘the headquarters of the noise of the whole apartment’),8 between the living room and his parents’ bedroom. Gregor finds himself wholly surrounded, once again a hostage of his own family.

Both doors are locked, however, possibly to protect his privacy and keep his family’s constant intrusions at bay. In this way, Gregor’s bedroom is his inner sanctum, a liminal space—neither fully inside nor outside the family circle—with the locked door serving both as a barrier and a threshold.

Above Gregor’s table hangs a picture he had recently cut from a magazine, showing ‘a lady in a fur hat and fur boa who sat erect, holding out to the viewer a heavy fur muff in which her entire forearm had vanished.’ This image, seemingly innocuous, takes on greater meaning in light of Gregor’s transformation. Here, as we’ll see even more strongly in Chapter 2, this picture is both an object of devotion and something potentially profane and ‘unclean.’ The lady’s fur wrappings suggest both luxury and animality, something weirdly erotic—perhaps a reminder of the thin line between human and beast, that echoes Georg’s and Karl’s sexual transgressions (in ‘The Judgement’ and Amerika, respectively). The fur muff, in particular, works like a metaphor for concealment and penetration, the disappearance of the arm suggesting an act of insertion, a covert sexual gesture concealed by the propriety of the setting. Locking himself away with this picture, free from prying eyes, was perhaps one of the last sources of pleasure for the travelling salesman…

The sudden arrival of the general manager or chief clerk (depending on translations—der Prokurist in the original text, which means something like deputy chief) is not just absurd; it represents a crucial moment and an escalation in the narrative. His visit transforms a private family crisis into a public judgment and humiliation. The general manager comes not merely as an individual but as a messenger, a representative of the firm and its mysterious ‘boss’ (an invisible character that foreshadows the inaccessible high court of The Trial, as well as the count and officials in The Castle)—the manager is, in essence, the mouthpiece of the debt that holds Gregor in bondage. He calls him from the other room, his voice, the exact inverse of Gregor’s, carrying the weight of institutional authority:

“Herr Samsa... What has come over you? You barricade yourself in your room, you reply to queries only with yes and no, you cause your parents onerous, unnecessary worries, and you are neglecting—let me permit myself to note—your professional responsibilities in a truly unprecedented manner. I speak here in the name of your parents as well as your employer and in all seriousness must ask you for a clear and immediate explanation. I am astonished, utterly astonished... To be sure, the boss did suggest one possible explanation for your absence this morning—it concerns the cash payments recently entrusted to your care... And your position is anything but secure. It was originally my intention to discuss all this with you in a private conversation, but since you compel me to waste my time here, I do not know why your esteemed parents should not hear of it as well. In short: your productivity of late has been highly unsatisfactory.

And the manager keeps harassing Gregor in his bed, continuously and almost literally twisting the knife, pouring criticisms and offloading grievances onto Gregor in front of his flabbergasted parents; and this allusion to a ‘cash payment’ Gregor might have mishandled—apparently not the original debt, but yet another claim hanging over Gregor’s head… At any rate, this visit only deepens Gregor’s isolation, victimisation, and quasi-immolation.

Meanwhile, Gregor remains caught in a sort of ‘double bind.’ He both seeks to fulfil and escape his obligations, to be both the perfect son and the liberated individual. This contradiction is precisely captured in his physical predicament—his new form makes work impossible while his mind remains fixated on his responsibilities.

The irony of being threatened about job performance and security, about being regarded as potentially redundant, while transformed into an insect reveals the absurdity of the entire system of obligation. Gregor’s position was never truly secure—his role as family saviour was always predicated on his continued ability to sacrifice himself for others, his ability (or rather inability!) to become the expiatory victim of his parents and employer.

Reaching the end of Chapter 1, the transformation of Gregor’s father from a defeated debtor into an agent of violence marks another crucial development in this sacrificial narrative. When Gregor finally emerges from his room, instead of recognition, the father responds with physical aggression, ‘uttering hissing sounds like a wild man.’ (‘wie ein Wilder’), driving Gregor back with a newspaper and walking stick, wielded (Kafka’s taste for slapstick comedy is evident in this scene) like the weapons of a circus tamer. However, this also underscores how swiftly the civilised elderly man can succumb to his primal and ruthless urges; his aggression becomes both personal and emblematic, revealing the violence that exists within familial and financial responsibilities.

As his father forces him back into his bedroom, we see the completion of the first stage of Gregor’s sacrifice:

then his father administered a powerful shove from behind, a genuinely liberating thrust that sent him flying, bleeding profusely, into the far reaches of his room. The door was banged shut with the stick, and then at last all was still.

This attack, which will be repeated in Chapter 2 with the apple-throwing incident, once again marks Gregor physically as a scapegoat. Yet unlike traditional sacrificial victims who are offered to the divine, Gregor’s ungezieferisation only emphasises his status: both victim through and through and unfit for proper sacrifice.

Through careful attention to Kafka’s language, we see how the story subverts traditional narratives of sacrificial substitution and atonement (from Isaac and the Ram to Iphigeneia at Aulis, to Jesus’s Crucifixion). Unlike Isaac, who was spared by the provision of a suitable sacrificial animal, Gregor becomes trapped in a perpetual state of unsuitable repayment. His transformation makes literal what was already true metaphorically—his reduction to a mere instrument of debt compensation had already made him less than human in the eyes of society.

So, ultimately, the horror of Gregor’s situation lies not in the physical transformation itself, but in how it reveals the dehumanising nature of financial and familial obligation. Without the traditional frameworks that gave meaning to sacrifice, Gregor’s suffering becomes merely absurd—a pointless metamorphosis that serves no higher purpose and neither achieves peace nor reconciliation within the community.

As we move into the two subsequent chapters, the implications of this failed sacrifice will become increasingly apparent. The question is not whether Gregor will be sacrificed—that process began, in fact, long before his transformation—but rather what happens to a society that can neither get any satisfaction from sacrifice nor redeem its victims, nor even acknowledge their humanity.

Since I started with Dante, and while I prepare my next post, why don’t you take a look at

’s Divine Comedy read-along?F. Kafka, The Metamorphosis, Norton, trans. S. Bernofsky.

S. Bernofsky, ‘On Translating Kafka’s The Metamorphosis’

V. Nabokov, Lectures on Literature.

R. Stach, The Decisive Years, ch. 14.

R. Girard, La Violence et le Sacré, Grasset, translated as Violence and the Sacred, Bloomsbury.

T. Todorov, Introduction à La Littérature Fantastique, Seuil, ch. 10.

"But Gregor’s transformation makes him simultaneously the perfect and the impossible scapegoat: perfect because he bears the community’s (his family’s) burdens, impossible because his very nature renders him ritually unclean."

This is a very interesting insight and it fits so well with what I see as an eternal Kafka theme of the subject being trapped between two opposing roles or identities, blocked and paralysed.

There is a tendency to go straight for the allegorical reading where Gregor simply represents the plight of the central European Jew, such as:

"A man could go to sleep an employed Jew and wake up the next morning as vermin. A Jew could study at the university and yet find himself called a dog. In German and Austrian anti-Semitic political publications, Jews were frequently referred to as “rats,” “mice,” “insects,” and “vermin.” If a person can go to sleep a Jew and wake up transformed into some kind of “vermin,” what is to prevent an animal going to sleep a dog and waking up a person? It is as if Kafka took that reality, the ever-present possibility of being referred to as some sort of animal, and pondered what it would be to truly become an animal"

Hadea Nell Kriesberg “Czechs, Jews and Dogs Not Allowed” in _Kafka's Creatures_, ed Marc Lucht.

This reading is certainly valid but I think it's much too obvious to be the reading we could settle on as 'definitive'. The idea that he is not simply a vermin in the eyes of European society from his condition of Jew, but also unclean to be offered as a sacrifice gives it that dimension that I consider to be truly Kafkian, where he takes that particular identity - Jew, Czech, German-speaker, European and expands on it through archetypal resonances. The scapegoat or sacrifice is one such - to be unworthy even as a sacrifice is typical of K's fascination with the frustrated destiny or desire.

So yours is a fascinating idea to be considered further. I'm very interested in two Deleuzian concepts in relation to K - minor lit and animality, and how they connect. This is another very interesting potential strand in that weave.

Heyyyyy!!! Where are you? You haven't posted in so long!